What is an index?

In financial markets, an index is an indicator of the overall change in the values of some or all of the securities listed on a particular market. The index is constructed as a portfolio in which each security is weighted according to its market importance.

Where have you heard about indices?

Everywhere. As an investor, you will be made constantly aware of the movements of indices during the course of the trading day and sometimes over a longer horizon. You may be invested in financial products such as index funds that are linked to one index or another.

What you need to know about indices...

Indices are designed to give an indication of the mood and performance of a particular market, with a net reading up or down once all positive and negative movements of individual securities have been added up.

Well-known stock indices include the Dow Jones Industrial Average and Standard & Poor's 500 in the US, the FTSE 100 in London, the DAX in Germany and the Nikkei 225 in Japan.

'Tracker' mutual funds and exchange-traded funds seek to mirror the construction of the index in question. Indices are used also to benchmark fund-manager performance.

Types of indices

There are hundreds of indices around the world, which have been created to track specific groupings of stocks. But other indices track everything from bonds and property to volatility. Indices tend to be grouped by geography, the size of their constituent parts or by their activity. The best known stock market indices in most countries will be made up of the largest companies or large caps, although indices of small and mid-caps feature too.

Indices can also be classified according to how their parts are weighted.

Market value-weighted index

The market capitalisation or market value (of equity) weighted index is the most common. In the case of stocks, each company is weighted by the total value of shares issued. So, say company A has issued 1 million shares that trade today at £5, giving it a market cap of £5 million. Company B has issued 15 million shares that are worth £1, giving it a market cap of £15 million. If an index was made up of these two companies, the combined market cap would be £20 million and A would have a weighting of 25% (£5m/£20m) and B a weighting of 75% (£15m/£20m).

The advantage of this type of weighting is that larger companies exert more influence. The downside is that sometimes one sector or company can come to dominate the index. The six largest companies in the FTSE 100 for example make up a third of the index. The S&P 500 is also market cap weighted. In the late 1990s, as the tech bubble grew, technology stocks started to dominate. The chart below shows the S&P 500 index from 1928 to the present.

Historically all of each company’s shares were included in the weighting but now many indices, including the FTSE 100, are float-adjusted. This means only shares freely available to trade are counted.

Price-weighted index

Price weighting is much less common today. Here the index is weighted by share price rather than by market capitalisation. The big drawback is that speculation and other factors can disconnect the share price from the intrinsic value of the business. A company trading at £10 per share will have twice the weighting of one trading at £5 per share.

The most famous example is the Dow Jones Industrial Average, which is made up of 30 of the largest companies in the US and accounts for around 25% of the value of the US stock market. The index however is no longer straightforward to calculate and does not simply take an average share price. A formula is now used to compensate for spin-offs, stock splits and other factors.

The chart below shows how The Dow has evolved since 1896 and the major influences on the index.

Investors should understand that market cap and price weighted indices provide different indicators. If the total market value of FTSE 100 companies fell by 20%, the value of the index would fall by 20%.

If the price of stocks on The Dow fell by 20% however, the index would not necessarily fall by the same amount. A $1 fall in the price of a $100 stock will have a greater impact on the index than a $1 fall in the price of a $10 stock despite the fact the first has fallen by 1% and the second by 10%.

The market cap approach therefore makes it easier to measure change across portfolios in percentage terms.

Equal-weighted index

Less common is the equal-weighted index, which assigns an equal value to all of the constituent parts. The Barron's 400 Index for example weights each of the 400 stocks by 0.25%.

This approach has gained in popularity due in part to the arrival of exchangetraded fund (ETF) options.

Composite index

As its name suggests, a composite index groups other indices or factors to gauge a particular market or sector over time. One of the best known is the Nasdaq Composite index, which uses a market cap weighting of around 5,000 stocks on the Nasdaq.

Fundamental index

We talked earlier about the potential problem of a disconnect between the intrinsic value of a company and its stock and the distortion this can create in an index. The latest thinking is to create an index based on the fundamental values of the constituent companies, such as book value or cash flow. Needless to say, this is the most complex approach to constructing an index and there are many options on how to weight components.

Different versions of indices

There are also several versions of some indices, including the S&P 500. Each iteration weights components slightly differently and might account for dividends and taxes for example to give a better indication of total return.

Well-known market indices

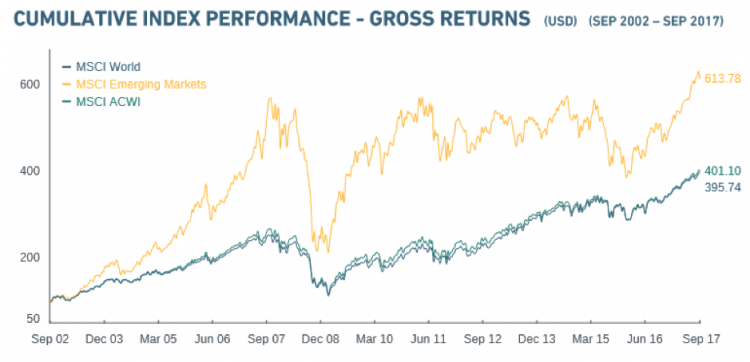

Indices can be classified by geography. Among the best known global indices, which include stocks from several regions of the world, are the MSCI World and the S&P Global 100. The chart below shows three variants of the MSCI. ACWI means All Country World Index. The World index is made up only of developed country stocks.

Some of the best-known share indices are national and are tracked closely by market commentators because they are believed to show investor attitude to economic conditions. They typically comprise large cap stocks from a variety of sectors in that country. Examples include the FTSE 100 in the UK, Nikkei 225 in Japan and the S&P 500 in the US.

Indices based on exchanges might also be familiar and include the NYSE US 100 and US Tech 100. The Euronext 100 and OMX Nordic 40 are actually based on groups of exchanges.

How indices help investors

Indices allow analysts and investors to compare investments and track market performance. Certain investors leverage such indices via exchangetraded funds or mutual funds. They also provide a useful benchmark to gauge a given stock against its sector, to judge how a fund manager is performing or for other financial instruments such as ETFs to track.

Index funds

These are a type of mutual fund whose components mirror a given index with the aim of replicating its performance over time. They typically offer low operating costs, in part due to low portfolio turnover, and reduce risk concentration. They follow predetermined rules irrespective of how the market is performing.

In contrast to actively managed funds, “indexing” is a form of passive investment. Many track well-known indices such as the S&P 500 while others for example track foreign stocks or the bond market.

Index funds are often regarded as ideal core investments for retirees due to their stable performance over the longer term.

The below chart shows a breakdown of the different funds the explicitly track FTSE indices.

Benchmarks

Indices are designed to allow investors to compare performance over time, or if you like to benchmark one company or sector against another. Most benchmarks in the investment world are indices but not all indices are benchmarks.

ETF.com explains that “a benchmark is an index that serves as the measurement yardstick for a portfolio by comparing portfolio characteristics such as returns, risk, component weights and exposure to sectors, styles and other factors to the benchmark”.

Investors can use benchmarks to let their portfolio manager know their broad goals and take decisions accordingly. The benchmark needs to reflect the investor’s risk appetite and budget and be suited to the investment style being considered.

Some portfolio managers will track the benchmark while others will aim to outperform, which carries a higher level of risk.