Is inflation about to rear its head again?

Inflation could be about to rear its ugly head again. Beneath the surface of the current spike in market volatility is the underlying risk that price pressures could be building once more across the global economy, especially in the United States.

Governments are causing it, the artificial intelligence investment boom is at the forefront of it, and central bankers risk enabling it. The global economy could find itself squeezed between positive demand shocks and negative supply shocks, skewing inflationary risks to the upside. The US Federal Reserve is beginning to wake up to the possibility. But it faces challenges and trade-offs if it is to remain committed to its foremost responsibility of maintaining price stability. As the battle to control inflation is waged, the markets could be set up for more volatility – with the final stretch of 2025 potentially a bumpy one for risk assets as a result.

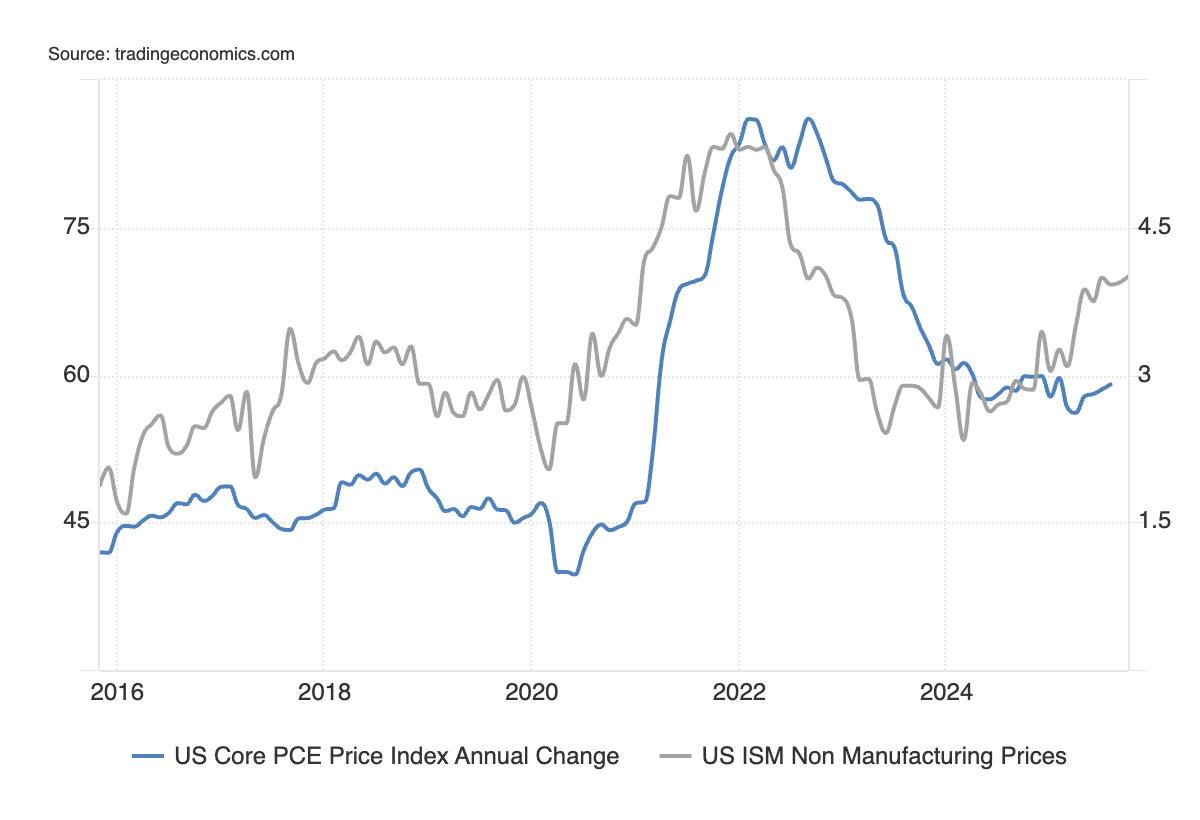

The data was telling market participants that inflation was still an issue. While some economies saw a successful return to target after the pandemic surge in prices, many did not. The US is the most important case in point. With the benefit of hindsight, US prices reanchored above target long ago. The trough in the US Federal Reserve’s chosen inflation gauge, the Core PCE Index, was 2.6% in April 2025. There were hopes that the slow decline in price growth was all down to the “last mile problem”; and with policy settings still considered notionally restrictive as the labour market weakened, the Fed decided it could confidently start cutting rates. A pick-up inflation, partially but not entirely due to tariffs, is now painting a picture of an economy that’s seeing prices reanchored in the high 2% range and moving away from target. A concerning detail in the recent ISM Services PMI data, for example, was a prices paid sub-index that hit the highest level since the end of 2022. This is inflation predominantly not generated by good prices – that is, tariffs – but consumer demand in the economy.

(Source: Trading Economics)

(Source: Trading Economics)

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

This isn’t a story confined to the United States, though. Other economies around the world and their policymakers are experiencing similar situations. Japanese core inflation remains around 3% and based on the last reading moving away from target but a sheepish Bank of Japan is keeping rates at levels that it itself describes as accommodative. The last UK inflation data had core price growth at 3.5% but the Bank of England is expected to cut interest rates next month as it confronts a stagflationary economic environment and focuses on the employment side of its mandate. Australian inflation just rose above target with the RBA backing off recent rate cuts as it forecasts above 3% underlying inflation until the end of next year. European inflation is at a respectable level but only managed to hit a cycle low of 2.3% with further rate cuts by the ECB still considered a possibility.

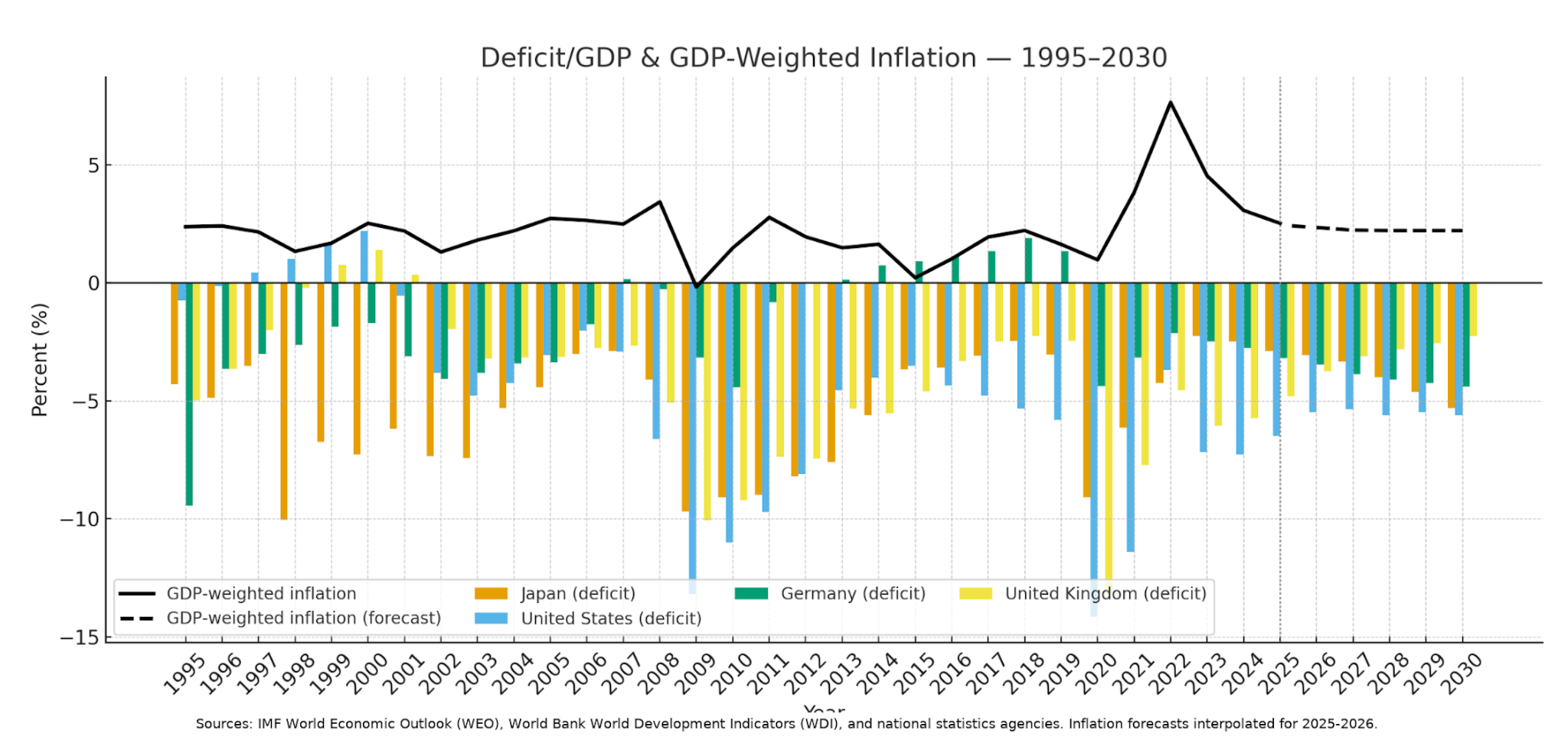

The level of prices around the world could be tolerated if there weren’t significant demand factors coming down the pipeline. Current budgetary plans across several developed economies point to a fiscal impulse akin to that which would normally be seen during economic slowdowns. Germany and Japan have pledged deeper government spending over the next few years as it looks to deepen domestic manufacturing capacity, especially in strategically and economically important industries, and boost defence. The US is planning to maintain deficit spending at between 5% to 6% of GDP, with offsets that were originally forecast to come tariff revenue being earmarked for cash handouts to households. The United Kingdom is the only major developed economy looking to seriously rein in the fiscal impulse but that’s only because it is in the midst of a fiscal crisis. These deep deficits are tantamount to fresh money being pumped into the global economy. All else equal, printing new money in an elevated inflation environment only means more inflation.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

The most troubling part of the problem is that the dynamic is structural in nature. There are several strong incentives for policymakers – both monetary and fiscal – to maintain loose policy settings. They range from well-meaning attempts to avoid the stagnation that plagued the global economy post-GFC, to the insidious elements of populist politics. However, arguably the biggest incentive comes in the form of the global artificial intelligence boom that is driving huge amounts of private and public money into AI infrastructure and creating a massive competition for physical resources. Private money is motivated by commercial competition in a bid to capture the returns on offer from artificial intelligence. Public money is being motivated by strategic and economic competition – the AI arms race between the US and China being the case in point. When incentives are all skewed in the same direction, it creates path dependency and then inertia. In the current context, the incentives are skewed towards continued big spending, competition for resources, and thus inflationary risks.

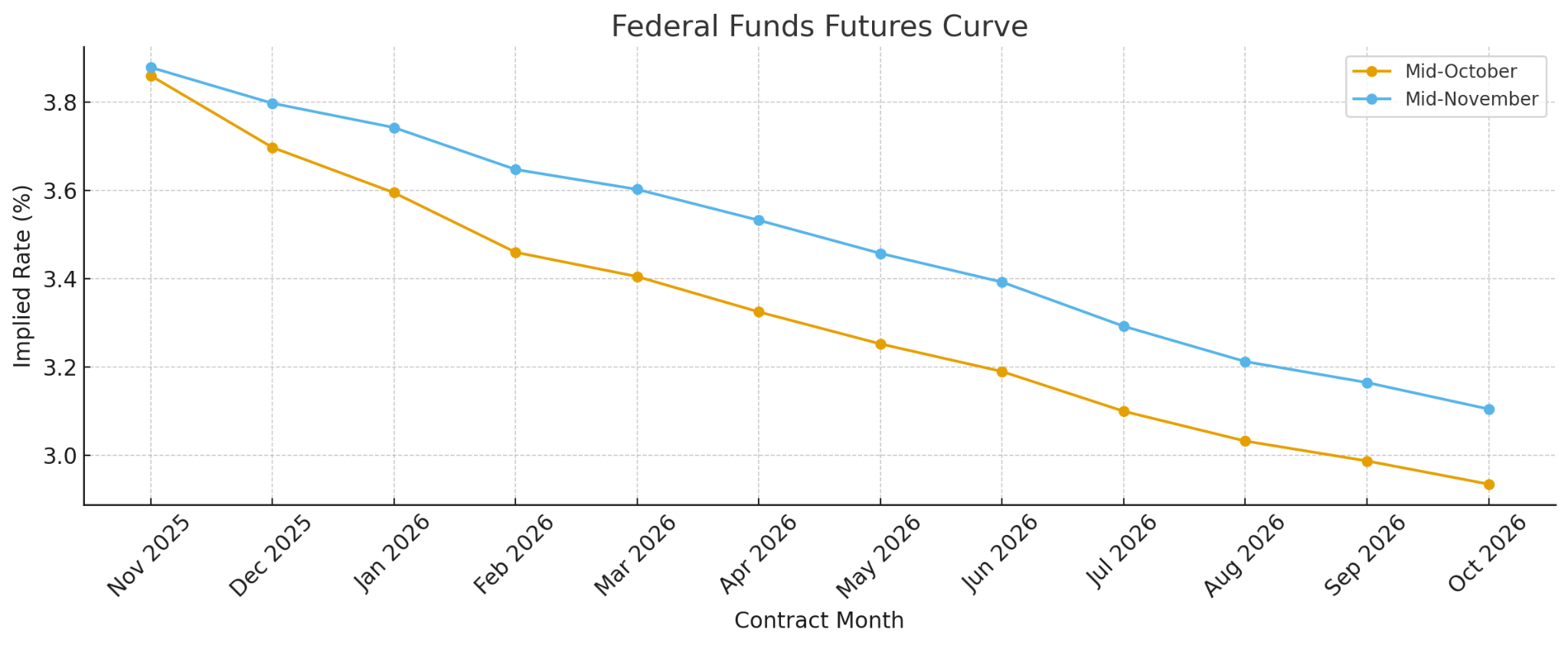

The US Federal Reserve is wising up to the situation, however. Chairman Jerome Powell’s warning following the last FOMC decision that an interest rate cut in December is “not a foregone conclusion” was a shot across the bow to a market that had been euphoric about what we have described as the run it hot trade – the rallying of everything from gold, to crypto, to stocks on the prospect that the Fed would cut rates deeply despite a strong fiscal impulse and above target inflation. The Fed can see the makings of another lift-off in inflation. And while it remains justifiably concerned about the US labour market as it seeks to ascertain the cause of its recent malaise – whether related to weaker demand, changes to immigration policy, or even the impact of artificial intelligence – it sees the risks to both sides of its mandate. As a result, the Fed is shifting its stance to maximise policy optionality, and even tighten financial conditions, by talking tough and pulling cuts implied in the rates curve out of the market.

(Source: Capital.com, CME Group)

(Source: Capital.com, CME Group)

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

A more hawkish and inflation focussed Fed sets the markets up for possible volatility in the short-term and downside risks in the longer run. One major reason for the recent equity market sell-off, not to mention the drop in things like gold and Bitcoin, is market participants are heeding the US Federal Reserve’s warning. It’s a partial reversal of the “run it hot” trade. The implied probabilities of a December rate cut have fallen from nearly 100% towards the end of October when stocks were scaling record highs to less than 50%, implying the markets are positioning for a likely rate hold at that meeting. Still, the markets are discounting more cuts to come from the Fed in 2026, with the futures curve implying the possibility of three more cuts to come next year. If inflation does indeed rear its head again, a credible Fed would have to talk down the odds of these cuts too. That would spell further trouble for equities everywhere and set the stage for a much more bearish market.