What currencies are pegged to USD?

Learn all about the US dollar’s pegs, including why countries peg their currencies to USD, and how it can affect forex trading.

Some countries and territories peg their currency to the US dollar to help stabilise exchange rates and support economic policy. While this can offer predictability, it also limits monetary flexibility and introduces external risks.

In this guide, we’ll cover how USD pegs work, which currencies are pegged to the dollar, why countries choose this approach, and what it means for forex traders.

What does it mean to peg a currency to the USD?

When a currency is pegged to the US dollar, its exchange rate is fixed or closely managed by the country’s central bank. Instead of letting market forces decide the rate – as with floating currencies – the bank intervenes to keep the value stable against the dollar.

A hard peg holds the rate constant, while a soft peg allows limited fluctuations within a set range. Pegging to the USD helps provide stability and predictability for trade, investment and economic policy – but can limit a country’s control over its own monetary decisions.

Why do countries peg their currencies to the USD?

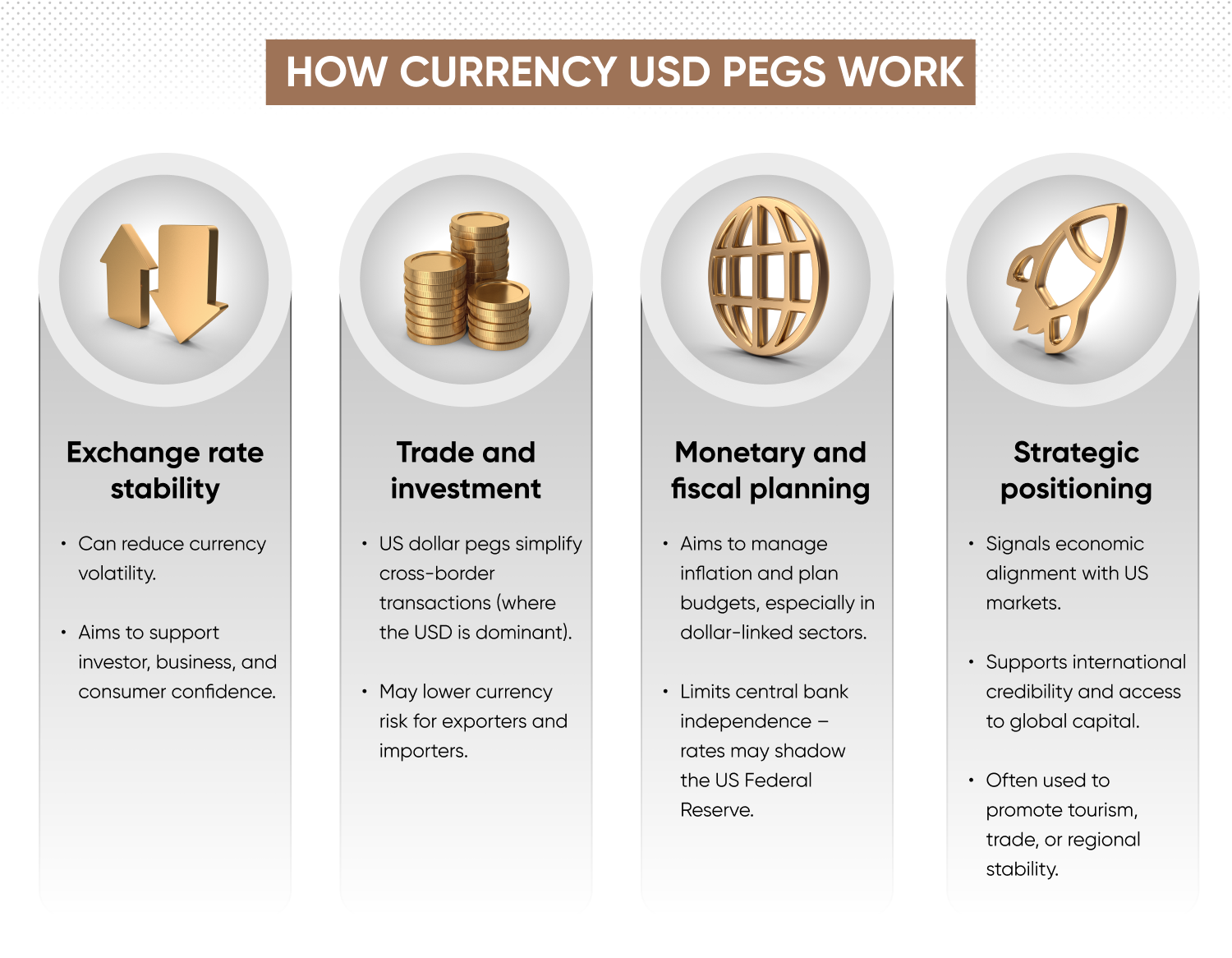

A number of central banks peg their currency to the USD as part of a broader economic strategy, with reasons including stability, trade, and policy management. Here are some economic factors influenced by USD pegs:

Stability in exchange rates

A USD peg can help reduce the risk of sudden exchange rate movements. For economies with a history of currency volatility or inflation, linking to the dollar anchors the local currency to one of the most traded currencies in the world. Such stability can bolster confidence among businesses, investors, and consumers. However, pegs can introduce risks if local economic conditions diverge from those of the US.

Facilitating international trade

The US dollar is the world’s leading reserve currency and is used in a significant share of global transactions. By pegging to the dollar, countries may find that cross-border trade and investment become simpler, particularly if their external obligations or major trading partners use the dollar.

It reduces some of the currency risk for importers and exporters, who know their local currency’s value against the dollar is less likely to swing unexpectedly. This predictability can attract foreign investment and lower transaction costs.

Economic and policy objectives

Pegging to the USD is also a tool for monetary policy. For some economies, especially those that rely on exporting goods or services priced in dollars, a stable exchange rate helps control inflation and plan public finances.

Central banks that maintain a peg may need to hold substantial dollar reserves and intervene in currency markets to keep the rate on target. However, maintaining a peg often reduces a country’s monetary policy independence, as domestic interest rates may need to follow those set by the US Federal Reserve.

Strategic alignment

Some countries peg to the USD to signal economic stability or align more closely with major trading partners. In certain regions, a peg can support links to global markets or tourism, while for others, it can help enhance the country's economic credibility to international investors or donors.

List of currencies pegged to the dollar

Here’s a list of currencies pegged to USD, including hard pegs, soft pegs, and 1:1 pegs, as of 16 June 2025. This list is not exhaustive, but it broadly represents the scope of the US dollar’s role in the global currency landscape.

Hard pegs to USD

A hard peg involves fixing the currency at a constant rate to the USD, maintained with minimal or no deviation. Central banks actively intervene to sustain this fixed rate.

|

Currency |

Code |

Peg since |

1 USD equals |

|

Bahraini dinar |

BHD |

1980 |

0.376 BHD |

|

Saudi riyal |

SAR |

1987 |

3.75 SAR |

|

UAE dirham |

AED |

1997 |

3.67 AED |

|

Qatari riyal |

QAR |

1981 |

3.64 QAR |

|

Omani rial |

OMR |

1986 |

0.385 OMR |

|

East Caribbean dollar |

XCD |

1976 |

2.70 XCD |

|

Aruban florin |

AWG |

1986 |

1.79 AWG |

|

Barbadian dollar |

BBD |

1975 |

2.00 BBD |

|

Cayman Islands dollar |

KYD |

1974 |

0.833 KYD |

|

Djiboutian franc |

DJF |

1974 |

177.72 DJF |

Bahraini dinar (BHD)

Pegged since 1980 at 0.376 BHD per USD. Supported by Bahrain’s central bank with significant reserves, this peg aims to stabilise trade and investment while providing consistent value and reduced volatility, which are crucial for a trade-focused economy.

Saudi riyal (SAR)

Saudi Arabia’s currency has been pegged at 3.75 SAR per USD since 1987. The Saudi central bank actively manages large foreign reserves to uphold the peg, offering monetary stability and predictability to the Kingdom’s oil dependent economy.

UAE dirham (AED)

Since 1997, the UAE dirham has maintained a fixed peg of 3.67 AED per USD. Managed by the UAE central bank, the peg provides stable economic conditions and simplifies international trade, particularly within its oil-exporting sectors.

Qatari riyal (QAR)

Qatar’s currency peg at 3.64 QAR per USD was introduced in 1981, and was officially fixed to the US dollar in 2001. The central bank’s consistent intervention helps secure stability and confidence in the currency, underpinning Qatar’s financial sector and hydrocarbon trade.

Omani rial (OMR)

Pegged at 0.385 OMR per USD since 1987, Oman’s central bank actively maintains this fixed rate. The peg supports stability, reducing exchange-rate uncertainty for investors and trading partners, especially in energy markets.

East Caribbean dollar (XCD)

The Eastern Caribbean Central Bank pegs the East Caribbean dollar at 2.70 XCD per USD, a rate established in 1976. This consistent rate helps stabilise trade and financial relationships among the eight territories using the currency.

Aruban florin (AWG)

The Aruban florin has held a fixed exchange rate at 1.79 AWG per USD since its introduction in 1986. The peg is maintained by Aruba’s central bank to promote economic stability, crucial for the island’s tourism-driven economy.

Barbadian dollar (BBD)

Since 1975, Barbados has maintained a stable peg of 2.00 BBD per USD. Managed by the Central Bank of Barbados, this peg facilitates international trade, stabilises inflation expectations, and supports tourism and investment flows.

Cayman Islands dollar (KYD)

Pegged since 1974 at 0.83 KYD per USD, the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority maintains this peg to support its significant financial services sector by reducing currency risk.

Djiboutian franc (DJF)

The Djiboutian franc has been pegged at 177.72 DJF per USD since 1974. This peg supports Djibouti’s strategic role in regional logistics and trade, ensuring predictable currency values essential for economic planning and growth.

Soft pegs to USD

A soft peg allows the currency to fluctuate slightly within a narrow, controlled band against the USD. Central banks manage this band closely but with more flexibility than a hard peg.

|

Currency |

Code |

Peg since |

1 USD = |

|

Hong Kong dollar |

HKD |

1983 |

7.75-7.85 HKD |

|

Honduran lempira |

HNL |

2011 |

Crawling peg |

|

Nicaraguan córdoba |

NIO |

1991 |

Crawling peg |

|

Turkmen manat |

TMT |

2015 |

3.5 TMT (managed) |

Hong Kong dollar (HKD)

Initially, Hong Kong maintained a currency board (hard peg) at 7.8 HKD per USD. In 2005, the ‘soft peg’ trading band of 7.75–7.85 HKD per USD was introduced. Managed closely by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, this supports currency stability that is critical for Hong Kong’s global financial-hub status.

Honduran lempira (HNL)

Honduras operates a crawling peg that was re-established in 2011, periodically adjusting the value of the lempira against the USD according to pre-set rules or economic indicators. This managed flexibility allows modest depreciation over time, balancing stability with adaptability to market pressures and economic conditions. The peg lets the lempira fluctuate against the US dollar by up to seven per cent annually.

Nicaraguan córdoba (NIO)

Nicaragua uses a crawling peg approach, with the central bank announcing a predetermined rate of depreciation for the córdoba against the USD. This controlled depreciation helps stabilise the economy while managing competitiveness in trade.

Turkmen manat (TMT)

Turkmenistan manages the manat’s exchange rate at around 3.5 TMT per USD. The Central Bank of Turkmenistan intervenes regularly, allowing limited fluctuation to maintain economic stability and manage domestic inflation pressures.

1:1 pegs to USD

A 1:1 peg sets the local currency exactly equal to one US dollar, creating the simplest and most direct form of currency peg.

|

Currency |

Code |

Pegged since |

1 USD = |

|

Bahamian dollar |

BSD |

1966 |

1 BSD |

|

Panamanian balboa |

PAB |

1904 |

1 PAB |

Bahamian dollar (BSD)

Pegged 1:1 with the USD since 1966, the Bahamian dollar circulates alongside USD domestically. This parity contributes to stability that supports tourism, international trade and investment, and may simplify currency management for businesses and consumers.

Panamanian balboa (PAB)

The balboa has been pegged directly 1:1 to the USD since 1904. Panama uses USD notes as legal tender, issuing balboa coins domestically.

Learn more with our guide to the world’s strongest and weakest currencies.

How pegged currencies affect forex trading

Pegged currencies can influence forex trading by often reducing volatility and leading to tighter spreads, which shapes traders’ strategies and risk management. For those using contracts for difference (CFDs) to access the forex market, understanding the impact of currency pegs is particularly important, as it can affect everything from trade frequency to risk exposure.

Forex CFD traders could also monitor for signals indicating possible peg adjustments or breaks. Central banks defending a peg may require substantial reserves and may intervene in the market when necessary. If market forces or economic pressures become unsustainable, adjustments or abrupt abandonment of the peg are possible, which may trigger sudden volatility spikes and significant trading risks.

Learn more about major forex currency pairs – including EUR/USD, GBP/USD, and USD/CHF.

Pros and cons of a USD currency peg

Currency pegs present potential advantages, as well as risks. Understanding both sides helps you assess opportunities and pitfalls when dealing with pegged currencies.

Pros of a currency peg

Stable trade environment

Pegging a currency to a major currency such as the US dollar can provide stability by minimising exchange-rate volatility. Exporters and importers benefit from predictable currency values, simplifying budgeting, pricing, and risk management. Stable rates encourage international businesses to invest confidently, fostering long-term economic growth.

Lower inflation risk

Countries with currency pegs may experience reduced inflation volatility. Anchoring their currencies to a stable foreign currency can limit extreme fluctuations in import prices, supporting steadier inflation levels and contributing to economic predictability. However, this effect depends on the credibility and management of the peg.

Enhanced investor confidence

Currency pegs reduce uncertainty for investors. Foreign investors prefer markets where currency risk is lower, as predictable exchange rates simplify financial planning and decision-making. This confidence depends on the perceived sustainability of the peg and the adequacy of foreign reserves. This can support sustained foreign direct investment, boosting economic stability.

Cons of a currency peg

Limited monetary flexibility

Pegging to the USD means compromising central bank autonomy in monetary policy. Central banks lose the freedom to set interest rates independently, potentially restricting their ability to respond effectively to local economic conditions, such as recessions or overheating.

Risk of currency misalignment

If market conditions significantly shift, a pegged currency might become overvalued or undervalued relative to economic fundamentals. Misalignment can result in uncompetitive exports, excessive imports, or unsustainable trade imbalances, creating severe economic strain over time.

High reserve requirements

Maintaining a currency peg requires substantial foreign exchange reserves. Central banks must intervene regularly, buying or selling their currency to defend the fixed rate. If reserves are insufficient, or if confidence in the peg’s sustainability weakens, the risk of speculative attacks and abrupt, damaging shifts increases.

Past performance isn’t a reliable indicator of future results.

FAQs

What is a USD currency peg?

A USD currency peg occurs when a country fixes its currency’s exchange rate directly to the US dollar, either rigidly (hard peg) or within a narrow range (soft peg). Central banks actively maintain this fixed rate through market interventions, using currency reserves to buy or sell their currency as needed.

Which countries peg to the dollar?

Several countries peg their currencies to the USD. Notable examples of hard pegs include Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, Qatar, and the Bahamas. Hong Kong maintains a currency board with a fixed exchange rate system. Some countries, such as Honduras, operate managed exchange-rate regimes that reference the US dollar but are not strict pegs.

Is a currency peg permanent?

No, currency pegs aren't necessarily permanent. While some have lasted decades, they depend on sustained economic stability, adequate reserves, and supportive monetary policy. If conditions change significantly, central banks might adjust or abandon pegs, causing sharp market volatility.

Why is the USD a popular anchor?

The USD is the most widely used global reserve currency and dominates international trade and finance. Its stability, liquidity, and broad international acceptance make it an ideal anchor, reducing risk and simplifying international business and economic policy management.

Can a country break a peg?

Yes, countries can and do break currency pegs when economic conditions make them unsustainable. A peg might be abandoned due to dwindling currency reserves, extreme market pressure, or changing economic policies. Breaking a peg can lead to potentially rapid currency value shifts and significant market uncertainty.