What is an investor and how do they influence markets?

John Pierpont Morgan (founder of JPMorgan) was once asked to forecast how the stock markets would perform and his response was, ‘It will fluctuate’. An investor embraces the risks of these market fluctuations, as they also present the opportunity for wealth creation.

Key takeaways

An investor allocates capital expecting returns through stocks, bonds, or financial instruments, earning via capital appreciation, dividends, interest, or compounding growth to build long-term wealth over time.

Unlike traders who profit from short-term price movements over days or minutes, investors take a long-term view spanning months or years, focusing on underlying asset value rather than fluctuations.

Investors are categorized as active (hands-on research to beat markets) or passive (mirroring market performance through index funds or ETFs), and as institutional (large organizations pooling funds) or retail (individuals).

Becoming an investor requires understanding risk tolerance and financial goals, opening a brokerage account, selecting aligned assets, and continuously learning about markets and risk management techniques throughout your investment journey.

Investor sentiment drives significant market movements, exemplified when Nvidia lost nearly $600 billion in value in January 2025; beginners can start with low-fee index funds or explore CFDs for leveraged trading.

What is an investor?

Investors play a pivotal role in the global financial markets, serving as the lifeblood of the economy. They shape market trends, fund innovative startups, contribute to business growth and influence how capital flows through the economy. Investors provide the liquidity necessary for markets to function, and their actions can determine the price of stocks, commodities and even currencies.

Are investors different from traders?

While both investors and traders participate in the financial markets, their approaches and time horizons differ. Investors typically take a long-term view – they aim to build wealth over months or even years. They ignore short-term price fluctuations and focus on the underlying value of assets and how this may increase over time.

Traders, however, aim to profit from short-term price movements, which could happen over days or even minutes. Many traders use CFD trading, a form of derivatives trading which enables them to speculate on both rising and falling markets.

Learn more with our guide on trading vs investing.

Types of investors

To truly understand what an investor is, it’s important to consider the types of investors. They can be broadly categorised based on their approach and scale.

Active investors

Active investors take a hands-on approach to managing their portfolios. They dedicate time to researching individual assets, reviewing earnings reports, staying informed on news, and monitoring market trends. Active investors often use technical analysis to identify patterns and trends in order to predict future price movements. Their aim is to beat the market.

Active investors sometimes use automated investing, using robo-advisors and other automated platforms to build and manage diversified portfolios based on their risk tolerance and financial goals.

Passive investors

Passive investors adopt a more hands-off strategy, typically using fundamental analysis to evaluate the underlying value of the asset to determine whether it is overpriced or underpriced. Their aim is not to beat the market, but to mirror its overall performance.

Some of the strategies include:

Buy-and-hold strategy: this involves purchasing assets and holding them for extended periods, ignoring short-term market fluctuations.

Index fund investing: investing in index funds or exchange-traded funds (ETFs) that track market indices, such as the US 500 for broad exposure and diversification.

Institutional vs retail investors

Institutional investors are large organisations that pool funds from their clients to invest on their behalf. Examples include asset management firms, hedge funds, and insurance companies. Institutional investors typically invest large sums of money and can significantly impact market movements.

Retail investors are individuals who buy and sell assets for their personal accounts. They typically invest smaller amounts than institutional investors and often use online brokerage platforms to manage their portfolios.

How do investors make money?

Investors can earn returns in several ways, depending on their strategy and chosen assets.

Capital appreciation (buy low, sell high): this is the one of the most common ways how investors make money. It involves purchasing an asset at a lower price and selling it later at a higher price. The difference between the selling price and the purchase price is the capital gain.

Dividends: many companies distribute a portion of their profits to shareholders. These dividend payments can provide a regular source of income.

Interest: investors who buy bonds or other fixed-income investments earn interest payments over time, which can be more predictable than dividends or capital appreciation.

Compounding growth: reinvesting dividends and interest earned can accelerate wealth growth.

Alternative income strategies: business investors may generate income through real estate, private companies or start-ups, although these investments often have lower liquidity but higher potential returns.

How to become an investor

Becoming an investor is more accessible than ever, thanks to online platforms and educational resources.

- Step 1 - understand your risk tolerance and financial goals:your comfort level with risk and the importance of the funds to your lifestyle will shape your investment strategy.

- Step 2 - open a brokerage account:choose a reputable online broker and practice on a demo account.

- Step 3 - select assets and build your strategy:choose investments that align with your risk tolerance and goals.

- Step 4 - continuously learn about the markets:use market guides to understand how assets behave, investment strategies, and the factors that influence prices. Don’t forget to learn about risk management techniques.

What is investor sentiment?

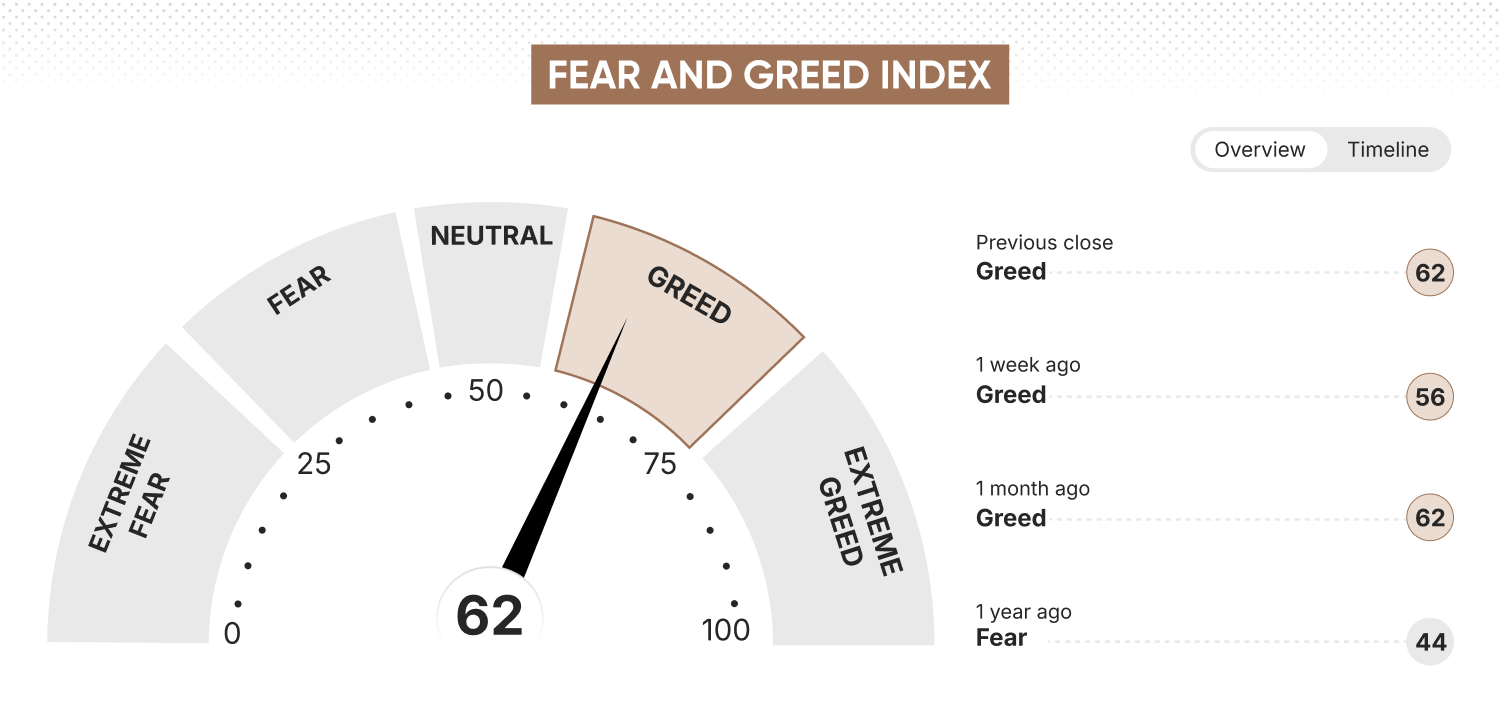

Investor sentiment reflects the collective mood – whether optimistic (bullish) or pessimistic (bearish) – towards a particular market or asset.

Investor sentiment can influence market behaviour and lead to significant price swings. Positive sentiment can drive prices higher, while negative sentiment may cause declines.

Real-world applications of investor behaviour

Investor sentiment can be a powerful market driver. For instance, in January 2025, the launch of DeepSeek by a Chinese startup sent US tech stocks sharply lower, with the US Tech 100 falling more than 3%. Nvidia saw its largest single-day loss in history, wiping out nearly $600 billion in market value.

Investor sentiment also played a role in Amazon’s stock hitting new highs in April 2020 during the pandemic and bitcoin reaching $82,000 following Donald Trump’s US election win.

Institutional investors often use sentiment analysis as a tool for investment decisions. Retail traders can access tools like CNN’s Fear and Greed index to gauge market sentiment.

The rise of Reddit’s r/WallStreetBets showed how collective retail investor sentiment can move markets, as seen in GameStop and AMC stocks, which experienced dramatic price swings driven by collective sentiment rather than fundamentals.

What are the best investment strategies for beginners?

There is no single ‘best’ investment strategy, as it depends on individual goals and risk tolerance. For beginners, index funds or ETFs are a popular choice for passive investors, offering broad market exposure with low fees. These funds are ideal for those looking to build wealth steadily without needing to pick individual stocks.

For active investors, investing in individual stocks or bonds can offer greater growth potential, but it requires more research and carries more risk. Dividend investing is another option, where you invest in stocks that pay regular dividends, providing both income and potential price appreciation.

No matter your strategy, starting with virtual money on a demo account can help you practice and understand how the market works without any risk.

Exploring CFD trading

Active traders may consider derivatives such as contracts for difference (CFDs), which give you the opportunity to profit from both rising and falling markets without taking ownership of the underlying asset.

A key feature of CFDs is leverage (also known as margin trading), which can give traders exposure to the price movements of large positions with only a small outlay. Leverage increases potential profit, but also amplifies the chance of losses, making it risky. Find more about CFD trading.

You can open a demo account with Capital.com for risk-free trading and become familiar with how CFDs and markets work.

FAQs

What is the difference between an investor and a trader?

Investors typically hold assets for extended periods, with the aim of long-term wealth creation. Traders aim for short-term profits from frequent buying and selling.

What are the risks associated with investing?

Common risks include market risk (the risk of overall market decline), inflation risk (the risk of inflation eroding purchasing power), liquidity risk (the difficulty of selling an asset quickly without a significant price loss), and company-specific risk.

Can anyone become an investor?

With the right education, tools, and strategy, anyone can start investing, even with a small amount of capital. However, investing is risky and participants must be comfortable with the risk to their capital involved.

How does investor sentiment affect the stock market?

Positive sentiment moves stocks higher, while negative sentiment can exert downward pressure.