Trade with a trusted global broker

Join a community of 740,000+ traders from around the world. Our customers love us so much, they’ve traded over $1tn in volume with us.

Authorised and regulated by the Securities Commission of The Bahamas (the SCB)

Join a community of 740,000+ traders from around the world. Our customers love us so much, they’ve traded over $1tn in volume with us.

Authorised and regulated by the Securities Commission of The Bahamas (the SCB)

Showing our 4 & 5 star reviews. The specific details of the user have been intentionally anonymised to safeguard their privacy pursuant to GDPR requirements.

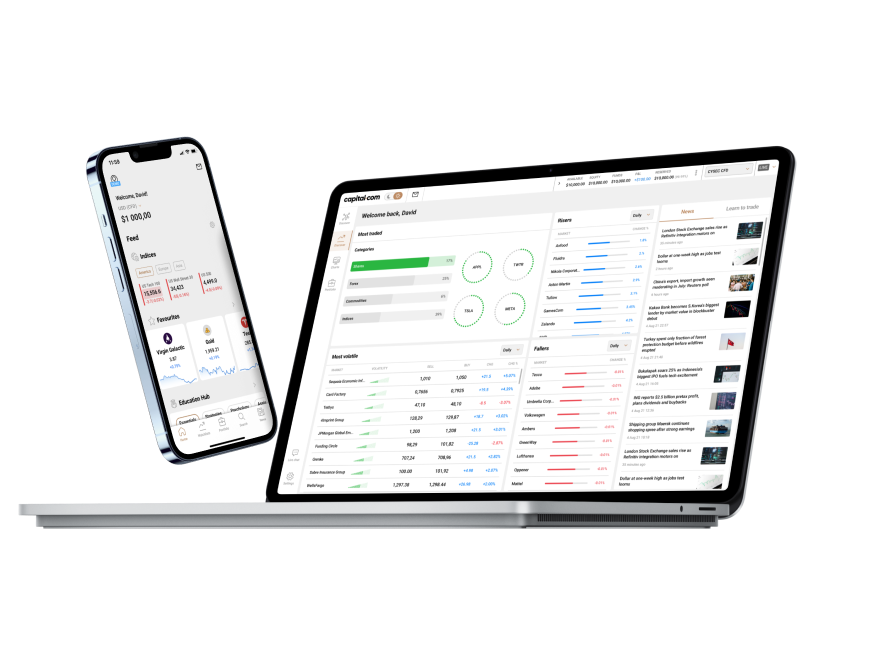

The ideal service, tools and resources to further advance your skills.

Sharpen your analysis with an array of intuitive charts, drawing tools and 100+ indicators.

Control larger positions with low margins on selected markets. Leverage magnifies both profits and losses. Limits may apply.

Our knowledgeable team is available 24/7 to assist you.

Monitor the price movements of your favourite assets and stay on top of your strategy.

99% of withdrawals are processed within 24 hours, according to our internal server data from 2024.

Start your trading journey with Capital.com.

Build your trading experience with ease, risk-free.

Learn key concepts via accessible courses, webinars, quizzes and videos.

Enjoy knowledgeable and friendly support, around the clock.

Stay comfortable with your exposure and trade using flexible sizings.

Use stop-losses1 to limit your downside when the market goes against you.

1Stop-losses may not be guaranteed